Essays on Leaves Acquired from the University of Chicago

In the twentieth century, the University of Chicago

special collections processed and held in its collection two leaves

from the Book of Mormon. The leaves are nonsequential. The first

bears text of what is now Alma 3:5–4:2, and the second of what is

now Alma 4:20–5:23. In

summer 1984, the University of Chicago sold these two leaves to The

Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. Around the time of the

sale, officials at both the University of Chicago and the church

determined that the leaves were likely authentic pieces of the

original manuscript of the Book of Mormon. Anomalies in the text,

however, have led some to believe these leaves (referred to here as

the “Chicago leaves”) are forgeries. The Chicago leaves have

sometimes been associated with Mark Hofmann, who in the 1980s forged

a number of documents relating to Latter-day Saint and American

history, though there is no evidence that the leaves ever passed

through Hofmann’s hands, nor is there any other documented

connection between the leaves and the infamous forger.

Scholars disagree about the authenticity of the Chicago leaves.

Because of their questioned status, the images and transcripts of

the leaves are presented as an appendix in this volume. We present

by way of introduction to the images and transcripts two

examinations of the evidence, one written by each of the volume’s

editors. With these two essays, readers and scholars may evaluate

for themselves the complex history and characteristics of the

Chicago leaves.

Photographs and transcripts of the leaves

are presented in the same manner as in the

rest of the volume.

Evidence for the Authenticity of the University of

Chicago Acquisition

Robin Scott Jensen

The provenance of the leaves acquired from the University of

Chicago—as well as similarities between the Chicago leaves and other

leaves from the original manuscript and forensic testing performed

on the leaves—strongly indicates that they are an authentic part of

the original manuscript of the Book of Mormon. Further, textual

analysis of the leaves offers important clues as to why some textual

anomalies in the manuscript might exist. While some anomalies in the

text raise questions about the leaves, these anomalies are

explainable and do not outweigh the considerable evidence of the

leaves’ authenticity.

It is unclear when or how the University of Chicago

acquired the leaves, though internal university records indicate

that they were likely “a gift from a noncommercial and

non-professional source.” Asked about the provenance of the

leaves, Robert Rosenthal, the head of the university’s special

collections in the 1980s, stated that “the document had been in [the

University of Chicago’s] collection since the 1920’s.” Rosenthal was very familiar with

the leaves and had in fact taken an interest in them when he began

work at the university in the 1950s. He had even tried,

unsuccessfully, to determine their history prior to their

acquisition by the University of Chicago. Physical evidence supports

Rosenthal’s assertion that the leaves were in the collection by the

1920s: The catalog card describing the leaves, which was created by

university library staff, matches the type and format of other cards

produced by the library from roughly 1923 to 1929. The Chicago leaves had apparently been

processed by special collections staff by the 1950s—a Library of Congress call number

was assigned to the two leaves, and staff assigned such numbers to

items in the codex manuscript collection (of which the Chicago

leaves were a part) only before the 1950s. After a theft in their collections around

1965, Chicago library staff began marking their manuscript holdings

with an invisible security mark meant to be seen under ultraviolet

light. The verso of each of

the Chicago leaves bears this security mark (see figure 1). The

known provenance of the leaves places them firmly in the custody of

the University of Chicago for much of the twentieth century.

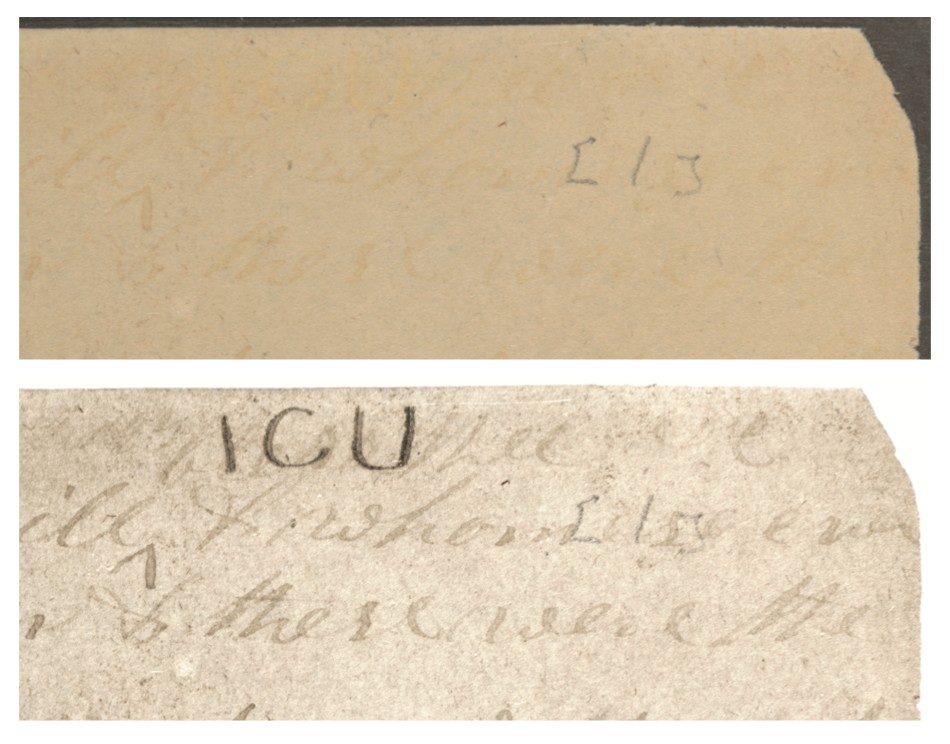

Fig. 1. The upper right corner of page [2] of the University of Chicago leaves under

visible (top) and Ultraviolet light (bottom). The “ICU” security

mark added by the University of Chicago is visible only under

ultraviolet light.

The physical characteristics of the Chicago leaves

closely match those of other pages of the original manuscript in

significant ways. The handwriting on the Chicago leaves appears to

be that of , who acted as scribe

for most of the original manuscript. The two Chicago leaves

measure at their largest 12¾ × 7⅛ inches. No other leaves are extant

from either the gathering that would have contained the Chicago

leaves or any adjacent gathering, making impossible a definitive

comparison to nearby leaves. The full height of the Chicago leaves

does, however, match exactly that of other known leaves from the

book of Alma in the original manuscript. The width of the Chicago

leaves in their original state is not determinable, since the sides

of the Chicago leaves have

been either trimmed or damaged. Manuscripts that underwent

conservation treatment in the mid-twentieth century often had their

edges trimmed.

Damage to the Chicago leaves also matches the pattern

of wear on the subsequent leaves of the book of Alma in the extant

pages of the original manuscript. While some portions of the leaves

are better preserved than others, it appears that the manuscript as

a whole sustained consistent patterns of damage while its leaves

were stored together. When deposited in the cornerstone of the

Nauvoo House, the manuscript was described as being complete,

without mention of any damage.

Over the decades during which it was in the cornerstone, the

manuscript sustained significant damage. Some portions, such as

parts of 1 Nephi, are still mostly intact, while other leaves show

significant wear. Some damage appears throughout many of the

gatherings and likely occurred while the manuscript leaves were all

stored together. For instance, many leaves, including the Chicago

leaves, are missing the upper right portion of the recto and contain

a hole in the lower center portion. The patterns of damage on the

Chicago leaves indicate that the leaves are authentic and were

stored with the other pages of the manuscript when they were

initially damaged (see figure 2). As leaves or gatherings were

handed out piecemeal, those individual portions sustained their own

unique damage, depending on the conditions in which they were stored

or displayed. The Chicago leaves also appear to have sustained

unique damage after they were separated from the rest of the

manuscript. The two leaves appear to have been stored together without the missing middle

leaf for enough time that fragments of the second leaf have adhered

to the first leaf. A small fragment from the second leaf has somehow

become attached to the verso of the first leaf, making it look as if

a hole has been patched near the bottom of the first leaf.

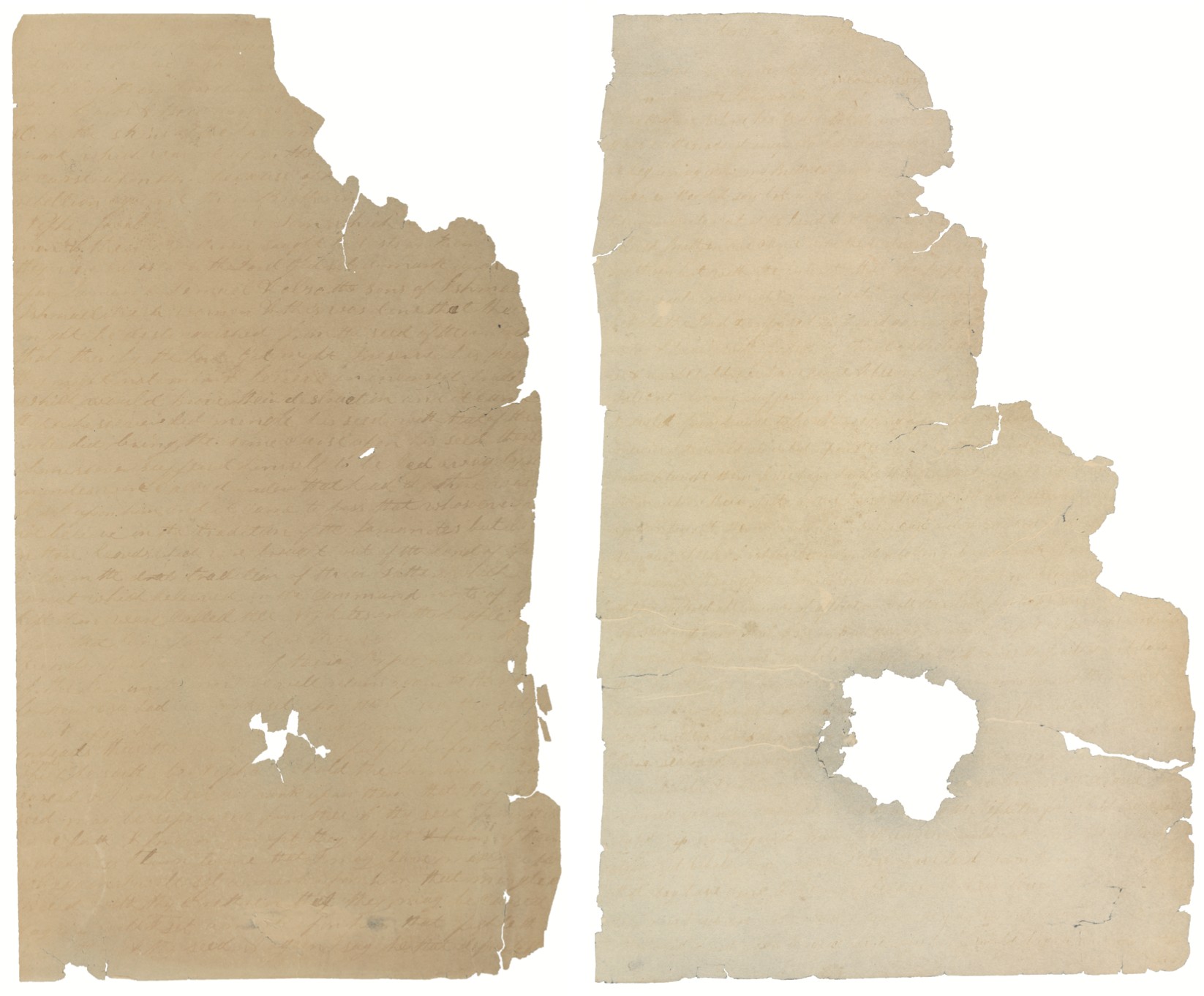

Fig. 2. Damage to the Chicago leaves (left) mirrors the damage to later pages

of Alma in the original manuscript of the Book of Mormon, such as

page [271] (right).

Several years after the arrest of Mark Hofmann, Royal

Skousen alerted leaders of the Church Historical Department to his

belief that the Chicago leaves were forgeries. In 1989, the Church Historical

Department arranged for forensic testing to evaluate the

authenticity of the leaves. George J. Throckmorton, a forensic document

examiner for the Salt Lake City Police Department who had been

instrumental in detecting Hofmann forgeries in the mid-1980s,

subjected the leaves to a battery of tests. His report was

inconclusive.

On Throckmorton’s recommendation, staff at the Church

Historical Department then hired Roderick J. McNeil, an analytical

biochemist, to perform Scanning Auger Microscopy (SAM) on the

Chicago leaves. SAM measures the ion migration of iron gall ink into

the fibers of paper and compares that with measurements of

contemporary documents that are known to be authentic, in order to

determine when the ink was originally inscribed on the paper. McNeil had

assisted in Throckmorton’s mid-1980s investigation of Hofmann

forgeries by performing SAM testing on documents suspected to be

forged. Throckmorton validated McNeil’s methods with a blind test of

documents; he found that McNeil’s analysis matched the known facts

about every one of the documents. When McNeil

analyzed the Chicago leaves in 1989, he concluded that they were

inscribed in 1830, plus or minus five years. McNeil further stated

that “the results from all the samples were very consistent and I’m

confident that the results are accurate.” Summarizing the results of all the testing—and

informed by correspondence with the University of Chicago about the

leaves’ provenance—senior Church Historical Department staff member Glenn N. Rowe wrote in

May 1990 that “all pieces appeared authentic.”

Provenance, physical characteristics, and forensic

analysis firmly establish that the Chicago leaves are at least one

hundred years old and apparently authentic. Textual analysis of the

Chicago leaves raises no strong evidence of their being a forgery.

In fact, some of the analysis reinforces their authenticity; a few

examples will be illustrative, though more could be included.

Several scribal mistakes indicate that the scribe writing on the

Chicago leaves was taking dictation, rather than copying from an

existing text. For instance, when Cowdery wrote “it came to not

<to pass> that not many days,” it seems that

he slipped and wrote what he immediately heard (“not”), failing to

capture the words between “to” and “not.” A

comparison of the text of the Chicago leaves with subsequent Book of

Mormon versions shows no obvious dependencies upon any subsequent

text, meaning that the Chicago leaves were not copied from the

printer’s manuscript, the 1830 edition, or later printed

editions—all of which contain unique, identifiable variations.

Finally, the scribal error rate in the Chicago leaves is similar to

that in other pages of the original manuscript (roughly one

misspelling per forty words), and the types of misspellings in the

Chicago leaves indicate an inexperienced scribe. Several errors in the Chicago leaves are distinct

from the types of mistakes that Cowdery typically made in the extant

manuscript. While there are errors throughout the original

manuscript of the Book of Mormon that are unique to particular

portions of the manuscript, the frequency of those unique errors is

higher in the Chicago leaves than in other portions of the

manuscript. Without the complete manuscript, it is impossible to

make definitive statements about the actual pattern of Cowdery’s

scribal work throughout the original manuscript. It is clear,

however, that the scribe of the Chicago leaves was inexperienced.

One example of a unique misspelling is the word “Morman.” Such a

misspelling is a glaring anomaly given that Cowdery otherwise

spelled “Mormon” consistently throughout the extant portions of the

manuscript, and some might see the error as evidence of forgery. But

the historical context of the creation of the Book of Mormon offers

a plausible explanation for this and several other discrepancies in

the Chicago leaves that might prompt some to claim the text is too

dissimilar to the rest of the manuscript.

After the loss of the initial portion of the Book of

Mormon manuscript, JS resumed dictation beginning at

the book of Mosiah. He dictated an unknown amount of the text of

Mosiah to his wife and his brother before arrived in , Pennsylvania, in early April 1829. It is unknown at what

point in the text Cowdery began taking dictation, but it is quite

possible that he was still settling into his role as scribe when he inscribed Alma 3–5, the

material covered in the Chicago leaves. Cowdery’s inexperience may

help make sense of the spelling of “Morman.” The first instances of

the proper noun “Mormon” following the loss of the initial portion

of the manuscript would have been in what is now Mosiah chapters 18

(twelve instances), 25 (one instance), and 26 (one instance). The

name was still relatively new, therefore, and if Cowdery began

serving as scribe anywhere between Mosiah 19 and 25, the name would

have been almost entirely unfamiliar to him when he got to the book

of Alma. If he began somewhere between Mosiah 27 and Alma 2, the

name would have been completely new to him. Since “Morman” is a

reasonable phonetic spelling and since there are other instances of

misspelling of proper nouns in the Book of Mormon text, such a

misspelling should not, by itself, be considered as evidence the

leaves are inauthentic.

The body of evidence supporting the Chicago leaves’

authenticity is at least as strong as and very often stronger than

the evidence for at least one other fragment of the original

manuscript that is accepted by scholars as authentic. Given the complexity of the relevant issues,

no single category of evidence can be conclusive in establishing the

authenticity of the Chicago leaves. Taken together, however,

provenance, physical characteristics, forensic testing, and textual

analysis strongly point to the Chicago leaves being an authentic

part of the original manuscript of the Book of Mormon.

Evidence against the Authenticity of the University

of Chicago Acquisition

Royal Skousen

The main problem with the two University of Chicago

leaves is that they exhibit too many unique properties, ones that

are exceptional, unexpected, or out of place, either for two leaves

of the original manuscript or for as

scribe. In this brief description, I will list some of these unique

properties. In this analysis, the symbol O

stands for the original manuscript and P for

the printer’s manuscript.

1. Two virtually complete leaves

instead of expected fragmentation. The shape of the

fragmented leaves is extraordinarily inappropriate. It explicitly

follows the shape of the 96-page gathering identified as A12.

As with typical fragmented leaves from gatherings, the outer leaves of A12 (both the first

leaves and the last ones) have disintegrated and broken up into

smaller remaining leaves and fragments. So we get only clumps of

fragments for the beginning and ending of what remains of the A12

gathering. Moreover, we get disintegrated fragments for the two

preceding gatherings (Alma 10:31–13:16 from A10 and Alma 19:3–20:22

from A11). And the same disintegration occurs for the gatherings

following A12: we get those few leaves from the beginning of Helaman

(from A13) and then large fragments in the Wilford Wood collection

from the end of Helaman and smaller fragments from the beginning of

3 Nephi (in A14). Or consider the fragments from 2 Nephi and Jacob

after the B2 gathering: from B3 through B6 the fragments

disintegrate, and in fact they clump together according to their

gatherings. And

the Ether gathering A17 (from the Wilford Wood collection)

disintegrates from both the front and the back of that

gathering.

Overall, the remaining leaves and fragments of O show that the small plates translation was on top and

best preserved for 1 Nephi, but then subsequent gatherings started

to disintegrate, as shown by all the fragments after the B2

gathering (that is, after the Franklin Richards gathering that

covers from 1 Nephi 14 to 2 Nephi 1). The B3 gathering includes the

Ruth Smith fragment, which is without a doubt legitimate. In his

examination of the Ruth Smith fragment in 1993–1994, conservator

Robert Espinosa identified this fragment as having paper type A (the

letter A is his identifying symbol for the

paper type). The surrounding gatherings have this same paper type:

from the Franklin Richards B2 gathering up through all the Wilford

Wood fragments from 2 Nephi through Jacob 4 (that is, from B2

through B5, but not B6, which covers portions of Jacob 6–7 and Enos

and has paper type C).

2. Imitating the fragment pattern at Alma

40–43. So how can we even get two leaves shaped like the

University of Chicago leaves? There is no way that two leaves in the

earlier gathering, A9, could suddenly take on the basic shape of the

A12 gathering that far away unless it had been moved into A12 prior

to O being placed into the Nauvoo House

cornerstone. In fact, based on the size of the hole that is 8–9

lines from the bottom, the Chicago leaves (three leaves originally)

would have been reversibly interleaved between page 302´ and page

307´ of A12. If this had happened, the missing upper and outer

corners should match, but the corners of the Chicago leaves extend

beyond the A12 pattern; that is, all the leaves in the A12 gathering

have a larger missing corner than the two University of Chicago

leaves. To be specific, we get the following differences for the

missing upper and outer corner of each leaf:

| 8 pages in A12 (301´–308´) | 13% of the text | lines 1–16 |

| 4 pages from Alma 3–5 | 8% of the text | lines 1–10 |

The University of Chicago leaves model the A12 ones, but they fail to

represent what could have reasonably happened to these leaves from

A9 as they disintegrated within the Nauvoo House cornerstone.

3. The middle leaf is missing.

Another big surprise is that the middle of the three Chicago leaves

is missing. All three leaves should be intact, but the second leaf

is missing. Where is it? I know of no example of any group of

attached fragments of O (either stuck

together or sewn together) that has lost a nearly completely formed

inner leaf. With the Andrew Jenson fragments, there were originally

five fragments stuck together for Alma 10–13, as well as three fragments originally in the same

condition for Alma 19–20. Apparently when

Jenson took the Alma 10–13 clump apart, the middle third fragment

disintegrated into small fragments, or somehow these disintegrated

fragments stuck to the other fragments and were later removed. In

any event, it does not look like Jenson saved them. On the other

hand, since the two outer leaves for the Chicago acquisition are so

well preserved, its middle leaf should also still exist.

4. A crowded text. There are too

many lines on each page. For these University of Chicago leaves,

which involve a widthwise fold of the original foolscap sheet, wrote 42 or 43 lines of text, which means

that the spacing between the lines was being economized. For other

pages in O with a widthwise fold and where

Oliver Cowdery was the scribe, the number of lines varies from 36 in

A12 to 39 in B2.

5. Trimmed leaves. The two

Chicago leaves are trimmed in the gutter, up to about 1.5 cm,

cutting off the text. The question is why? No other leaves or sheets

of O or P have ever

been trimmed. This difference, of course, cannot be assigned to , the original scribe.

6. The square notch. There is a

square cut in the gutter, an unusual notch, at the beginning of line

4 on the recto of the first leaf. This cannot be the jabbed hole

that would have put in the fold to

stitch the gathering together. Where could this have come from?

7. A papered-over hole in the

original manufactured paper. And then there is the original

hole in the first leaf that resulted from when the paper was

manufactured, near the bottom, centered on line 41, which was

patched up by pasting over the hole a small piece of paper and then

writing right across the patch. I have never seen any scribe or

anyone else taking this kind of trouble to deal with paper holes (or

parchment holes in manuscript books prior to printing). In contrast,

on line 10 of page 42 of O, when came to writing 1 Nephi 21:1, there was a

small hole in the middle of the line, and he simply skipped over the

hole when he wrote the word Mother: “from the

bowels of my Mo( )ther hath he made mention of my name”. For similar

holes in other places in O and P, Cowdery sometimes wrote the next character

above the small hole or below it, but he never made any effort to

patch up the hole.

8. The earliest extant spellings for Mormon

and Lamanites appear to

be distinctly altered. In this document, we have the

earliest extant instances of two very common Book of Mormon names,

including one that occurs in the title of the book:

Mormon written twice as

Morman: When we check every

legitimate instance of Mormon in ’s hand, whether

in O or P, we

find that it is always written as Mormon, smoothly and without any shakiness or

heavier ink flow (in other words, differently from these two

instances of Morman in the Chicago

leaves).

Lamunites and Lamun: The initial spellings for Lamanites and Laman take a u vowel for

the second a. In and of itself, this

is not unusual for :

he sometimes writes “everlasting love” as “everlusting

love”. But we do not transcribe such examples of Lamanites with a u because Oliver never overwrites these u-like a’s as

u’s. But in the Chicago leaves,

every sufficiently extant instance of Lamanites

(all 9 of them) is

spelled as Lamunites. In addition,

one instance of Laman is clearly

written as Lamun.

9. Too many unique misspellings.

When we consider the misspellings and scribal slips in the two

Chicago leaves, we find that 18 of them are strikingly different

from the spelling errors found elsewhere in O

and P. In the following analysis, each of the

unique errors is marked with an exclamation point (!). Whenever no scribe is specified, is assumed to be the scribe. I use the

following abbreviations:

| OC | (scribe 1 of O and scribe 1 of P) |

| JW | (scribe 2 of O) |

| CW | (proposed scribe 3 of O) |

| MH | (proposed scribe 2 of P) |

| HS | (scribe 3 of P) |

Franklin Richards acquisition, pages

263´ and 264´ (only 1 unique error for OC here in Alma

23–24)

| concerning | comcerning | a slip: 2× in O (Alma 23:3 and Alma 47:33) |

| prophecies | Prophesies | 9× in O, 13× in P |

| liveth | lieveth | 2× in O (Alma 23:6, both times), 3× in P |

| miracles | mir[a|u]cles | OC often writes a like u: “everlusting life” at Alma 33:23 in O |

| cities | Citties | 1× in O (Alma 23:13), 3× in P |

| weapons | weopans | 2× in O (Alma 23:13, both times); weopons: 26× in O, 16× in P |

| harden | heard[e|o]n | hearden: 2× in O, 7× in P; heardon: 3× in O, 3× in P |

| whithersoever | whitheersoever | a slip: er > eer: peerhaps (Alma 52:10, in O) |

| cities | Cittis | a slip: es > s (plural): eys, ons, Lamanits, embassis, Nephits, bons |

| ! curse | cures | a slip: se > es: coures [in place of course] (Alma 7:20, by MH in P) |

| stirred | stired | 6× in O, 13× in P |

| anger | angar | 15× in O, 1× in P |

| against | againts | a slip: 2× in O (Alma 24:2 and Alma 51:9), 1× in P (Ether 7:24) |

Ruth Smith acquisition, pages 55 and

56 (only 1 unique error for OC here in 2 Nephi 4–5)

| valley | vally | 15× in O, 32× in P |

| plain | plane | 3× in O, 8× in P |

| encircle | ensircle | 1× in O (2 Nephi 4:33), 1× in P (Alma 48:8); ensirceled: 5× in P |

| stumbling | stumbleing | 1× in O (2 Nephi 4:33), 6× in P |

| putteth | puteth | 1× in O (2 Nephi 4:34), 5× in P |

| exceedingly | excedingly | 22× in O, 71× in P |

| lest | least | 12× in O, 11× in P |

| ! buildings | bildings | bilding: 5× in O by CW; bildings: OC only here in 2 Nephi 5:15 |

Andrew Jenson acquisition, pages

228´–233´ (no unique errors here in Alma 10–13; difficult to

read)

| body | boddy | 8× in O, 1× in P |

| flaming | flameing | 2× in O, 3× in P |

| expedient | expediant | 18× in O, 54× in P |

| preparatory | preperatory | 1× in O (Alma 13:3); preperation(s): 10× in O, 21× in P |

When we examine the Chicago leaves, we get too many

surprises. Many of these are specifically found only in P, in either ’s or ’s hand, namely

and (instead of the ampersand), humbleed, mingleeth, and reccord(s); thus one can argue that the Chicago leaves

used P as a source for some of its

misspellings but assigned them incorrectly to .

University of Chicago acquisition, 4 pages (18 unique

exceptions)

| Amlicites | Amelicites (1×) | 3× in O (Alma 24:1, Alma 24:28, Alma 27:2) |

| ! & | and (3×) | never in O or P except 2× in P when OC overwrote an aborted word; MH and HS both have and along with & |

| armor | armour | 4× in O, 8× in P |

| baptize | baptise | 1× in O, 19 in P |

| ! began | bagan | 0× for all scribes in O and P |

| body | boddy | 8× in O, 1× in P |

| ! bondage | bondge | a slip: 0× for all scribes in O and P |

| declare | declair | HS, 2× in P (Mosiah 29:6 and Alma 5:1); OC, declaired: 2× in O |

| encircle | ensercle | 2× in O, 2× in P; ensercled: 4× in O; enserceled: 4× in P |

| encircle | insercle | 1× in O (Alma 34:16); insercled: 2× in P; insercles: 1× in P |

| experienced | experianced | obediance: 1× in P; disobediance: 2× in O and 2× in P |

| ! filthiness | filtheness | 0× for -eness for all scribes in O and P |

| ! foreheads | forheads | 0× for all scribes in O and P |

| fought | faught | 8× in O, 5× in P |

| ! guilt | gilt | 0× for all scribes in O and P |

| ! have | heave | a slip: 0× for all scribes in O and P |

| having | haveing | 23× in O, 50× in P |

| henceforth | hence forth | 1× in O (Alma 45:17), 5× in P |

| ! humbled | humbleed | 1× by MH in P (Alma 7:3), also by MH: trampleed, dwindleed |

| imagine | imagion | similarly by OC: immagionations, imagionations, imagioning |

| ! Ishmaelitish | Ishmaeliteish | a slip: 0× for all scribes in O and P for the ending -ish |

| ! Laman | Lamun | u clearly written instead of a: 0× for all scribes in O and P |

| ! Lamanite(s) | Lamunite(s) | u overwritten intentionally: 0× for all scribes in O and P |

| living | liveing | 3× in O, 6× in P |

| ! mingleth | mingleeth | 1× by MH in P (Alma 3:15); also by MH: trampleeth |

| ! Mormon | Morman | 0× for all scribes in O and P (never, even as a miswriting) |

| ! preach | spreach | a slip (blending preach and speech): 0× for all scribes in O and P |

| prophesy | prope{s|c}y | a slip, ph > p by OC: propesy: 3× in O; propesies: 3× in O |

| ! record | reccord | reccord(s): 0× for OC in O and P; 1× for MH in P, 2× for HS in P |

| remembrance | rememberanc | a slip, e > 0: audienc by OC in P (Ether 9:5); rememberance: 3× in O, 14× in P; rememberence: 1× in O (1 Nephi 2:24) |

| set | s[a|e]t | sat instead of expected set: 5× in the earliest text |

| separated | seperated | 1× in O, 3× in P |

| sought | saught | 1× in O (Alma 54:13), also 3× in P by MH |

| ! throughout | thruout | 0× for all scribes in O and P; also 0× for through spelled as thru |

| trodden | troden | 3× in O, 4× in P |

| view | vew | vews: 1× in P (2 Nephi 1:24) |

| villages | viliges | 1× by OC in P (Alma 23:14); also 1× by HS in P (Alma 5:0) |

| whomsoever | whomesover | 1× in O (Alma 36:3); also whome 1× in O and 2× in P |

| ! words | wordrs | a slip: no similar slip for all scribes in O and P |

| ! wrought | wraught | 0× for all scribes in O and P |

The Wilford Wood fragments are found on 58 pages of O, in 6 different places in the text, all in

’s hand; these fragments

account for 1.87 percent of the text, yet they contain only 4 unique

misspellings:

| Jacob 2:13 | apparrell |

| Jacob 7:27 | obiediance (or obiedience) |

| Helaman 16:8 | neaver |

| Ether 6:27 | annoint (2×) |

The Chicago leaves cover about 0.71 percent of the text. This means

that the spelling uniqueness for the Chicago leaves is roughly 13.6

times more frequent than what we get for the Wilford Wood fragments.

This is an extraordinary difference.

It is true that we have clear evidence for Oliver

Cowdery learning how to spell better, but this evidence is in P rather than in O.

Cowdery eventually learned to use standard spellings in P only because he was proofing the 1830

typeset sheets against his copy text, which was usually P. In O, on the other

hand, we have examples of him alternating his spelling (or

misspelling) for various words:

body ~ boddy

record ~ reckord

kept ~ cept

need ~ kneed ~ nead

saith ~ sayeth

led ~ lead

lest ~ least

fought ~ faught

dissent ~ desent

dissension ~ desension

anger ~ angar

angery ~ angary [in

place of angry]

Yet for all of these examples, never learned how to spell these words in O. There is only one word in O that Cowdery learned how to spell, exhort (but that occurred only near the end

of his scribing, in 1 Nephi 16–17, and just after had used the correct spelling, in 1 Nephi

15:25). From a statistical point of view, it is virtually impossible

to claim that Oliver Cowdery reduced his exceptional misspellings in

O to 1/13th the frequency in going from

Alma 3–5 to Alma 10–13.

10. Too many odd scribal slips. There are

additional problems with the Chicago leaves, some dealing with

scribal errors that never show up elsewhere in O and P:

Alma 3:20 (on line 11 on the verso of the first leaf):

now it came to not

<to pass> that not many days after

Elsewhere

and other scribes in O and P never miswrite “it came to pass” in

this way. Having written it came to,

they write pass without fail (1,393

times). There are only 6 scribal slips involving “it came to

pass”: (1) the scribe omits the to:

“it came pass” (3 times); (2) the scribe omits the initial

it came: “and to pass” (1 time);

(3) the scribe omits to pass: “it

came that” (1 time); (4) the scribe miswrites to as be: “it

came be pass” (1 time). Cowdery makes all of these errors

except for one instance of “it came pass”; in each of his

cases he immediately corrects his error.

Alma 4:1 (on lines 36–37 on the verso of the first Chicago leaf):

Now it came to

pass

Chapter <II>

Now it came to pass in the six sixth year of the Reign

of

There are 31 extant instances of chapter

beginnings elsewhere in O, from which

we can see that whenever JS came to

the beginning of a new chapter in his dictation, he

consistently told the scribe to write the word Chapter, and only then did JS start

to dictate the text of that new chapter, which the scribe

typically wrote down on a new line (29 times) but sometimes

on the same line after the chapter specification (2 times,

in the book of Ether). The situation here in Alma 4:1 is

unique, where either JS failed to dictate the word Chapter or the scribe failed to first

write down the word Chapter before

starting to write down the text of the new chapter.

Alma 5:14 (on lines 11–12 on the verso of the second Chicago leaf):

have ye spirit<ual>ly been [born of Go]d

There are only 2 instances in the manuscripts

where accidentally

miswrote an adverb ending in -ly: (1)

in O for 1 Nephi 19:2 he wrote particually in place of particularly, making a mess of the

final syllable for the adjective particular; (2) in P for

Moroni 10:17 he wrote severly instead

of severally, skipping the al of the final syllable of the

adjective several. In both these

cases, we have a simple scribal slip, and in neither case

did Cowdery correct his scribal slip (he may not even have

noticed it). But here in Alma 5:14, the error is clearly

objectionable: the -ly is directly

added to the noun spirit rather than

to the correct adjective spiritual,

thus creating the bizarre word spiritly, which is corrected.

11. Oddly written letters. There

are a large number of odd ways in which writes certain letters in the Chicago

leaves, ones that are not found elsewhere in his handwriting in O and P. For instance,

I note the following oddities for just the recto of the first leaf:

| line 12: | unusual extra loop in the s for also (also on line 3) |

| line 12: | unusual e in the first the |

| line 19: | unusual loop on the b of bring |

| line 24: | second r of Rcords is unusual |

| line 25: | unusual the |

| line 26: | unusual h in the |

| line 27: | unusual loop on the r of or |

Continuing in my transcript for the Chicago leaves, I

list about 30 similar oddities for the three other pages of this

document (including unusual letter forms, extra flourishes and

strange swirls as well as loops on letters, and even a loop

encircling a whole word). Most words may look like they are ’s, but there are also too many unusually

written words. This extensive phenomenon never appears in any of

Cowdery’s handwriting on other extant leaves and fragments of O.

One could propose an untested—in fact,

untestable—hypothesis here: is at

the beginning of his scribal work in the Chicago leaves, and

consequently he is creating all kinds of exceptions and oddities as

he takes down JS’s dictation. By adopting this

hypothesis, one can safely ignore all the unique spellings, weird

syntactic errors, and oddly written letters in the Chicago leaves,

along with the crowded text. No matter the uniqueness in the

handwritten text, it can be assigned to Oliver Cowdery’s beginning

as a scribe and thus dismissed. In this way, we can get rid of any

cases that we find inconvenient. Yet setting aside all these cases

of proposed uniqueness in the Chicago leaves means that no internal

textual evidence can ever disprove or call this document into

question. And this allows a weak provenance to trump all contrary

internal evidence from the written text itself. It is important to

remember that the provenance of the University of Chicago

acquisition comes down to the following fact: it was never publicly

known until its discovery in the early 1980s, in the same period

when numerous dubious documents (including other apparent fragments

from the original manuscript of the Book of Mormon) were suddenly

making their appearance. It is better to ignore this document until

all these oddities can be truly explained instead of simply

dismissed.